In a small town in Canada’s north, just below the Arctic Circle, two ravens are having a conversation. (A thIrd turns it into an argument.) Two planes fly overhead each day. The noon whistle still goes off at noon. There’s a grader for a single day at the start of summer, repairing the winter potholes. Distant voices from the other side of a hedge, soft enough to not be able to make any words out. That’s it.

An immense river sweeps quietly, continuously—like suction—through the vastness beyond the town, a reminder of what was there long before our time. Yet it also flows quickly, unerringly enough to offer a sense of possibility. Or—at the very least—a way out.

The town, and the silence. On your first night here, you heard a woman scream—a long, horror movie kind of shriek—at three in the morning, but it was dead quiet after that and hard to take seriously in all that twenty-four-hour summer light. A joke, surely. And no news the next day of anything bad having happened. The trust and comfort of living in a small town: if anything happens, you’ll hear about it. Perhaps not accurately, but it will be known. You can’t miss a thing.

It’s not just the quiet, the silence. It’s having all that land, all that space and water, all that emptiness and promise stretch out before you. The occasional Ford truck chortles past, and you try hard to think of another noise, but you can’t. Not even a dog barking here or there.

*

You once met a Dutch man at a party in Amsterdam who told you his whole life his dream had been to drive across Canada, to get away from the stifling crowdedness (his words) of the Netherlands—of the microchip-like quality to its landscape, all straight lines and predetermined—and get to a place that was raw, whose fate was as yet undecided, to stand somewhere and see no one.

This man, he drives from east to west, starting in Toronto. He drives and he drives and after a few days of only driving, of not really having paused, he decides that the prairie—which he’s reached by then—is the place to get out of the car and experience the vastness of the landscape. It’s his first time, and so it has to be just right. He turns off the highway and drives down a secondary road until he thinks he’s reached his place. He gets out of the car and walks into the middle of a field. He stands there, waiting. He doesn’t really know what he’s waiting for. Off in the distance, his car door dings. He looks around and sees nothing. No house, no tree, no hummock behind which something could be hiding. There is nothing to suggest human existence, or any life at all. Except for himself.

The thing he’s been waiting for starts to arrive. Slowly, slowly. But it’s not what he thought it would be. It’s panic. He starts to suffocate. Can’t breathe. He runs back to the car, the dinging door, and tears down that road back to the highway, never leaving the car again—except to gas up—until he reaches Vancouver four days later.

Turns out vastness is not what he wanted. Turns out a small, crowded, microchip-like country is just fine when presented with the opposite.

*

Maybe the desire for silence or solitude is cultural, or at least a question of habit. You think of the American cowboy, setting off into the lonesome, westward expanse. Then you think of the cars you encountered on desolate highways in South America, racing to catch up to the next one, not wanting to be alone. You think back to your own time in Holland, years ago. You were on one of the Frisian Islands, where the edge of a village met the sand and the sea. There was a café, which was full of Dutch visitors drinking espresso and coffee with milk. A split-rail fence surrounded it and the village—the kind you see in a horse paddock. The kind that wouldn’t keep much out. It was more of an idea, a demarcation that signalled something different was happening here than on the other side of this thing. Here = social. There = antisocial. You were standing on the outside—there—by the sand and the sea.

The tide started to go out, and fast. The Wadden Sea, between the islands and the mainland, is shallow, and sometimes a pathway between the islands emerges at low tide. So, when the water started to withdraw, you were suddenly faced with hundreds of metres of sand which, minutes before, had been submerged. You walked toward the beach and kept walking, following the water as it retreated, hardly keeping up. You turned around to see how far you’d come. You saw thousands of people hemmed in by the split-rail fence, having their coffee, surrounded by each other. You saw that you were the only one out on the sand, which by now stretched for a kilometre in either direction around you. You wondered if you’d done something wrong, if suddenly you’d start sinking into quicksand, or get swallowed up by a whale. But there was no danger. Just differing preferences of a place to be.

*

You have lived in remote places. You know vastness and silence. You crave it. But even though you might be comfortable in it, you know where the Dutch man was coming from. You might, like him, suddenly want the opposite when faced with it.

A few years ago, you were invited to spend a month working in a stone house in the middle of a remote valley in eastern Iceland. It was the middle of February and—inevitably—you arrived in the dark. A woman picked you up from the airport and you drove for about three-quarters of an hour through complete blackness. Not a light in sight, not another vehicle on the road. You arrived at the house and she let you in, then stepped back into her car and drove off. The sound of her car was quickly swallowed by the sound of a gust of wind moving up the valley. You stood there, waiting for the wind to hit. It did, and then it was gone.

And it was quiet again.

There wasn’t a single sound. Not one. Not a breeze, not a leaf whisking across the snow (it was a treeless place), not a shrew scampering by, not even a bird. You strained your ears for a sign of life. Anything.

The next morning a jet liner flew overhead, a flash in the sky, no vapour trail. So high it couldn’t be heard.

In the distance, the steeple of a small, red-roofed church poked up over a hill. Without the steeple, that absolute silence would have been okay. But the church was a reminder of humanity, and made it even more obvious that nothing alive could be heard. And a sort of current ran through you when you saw it, a visceral, uncontrollable response. A physical resistance to the silence.

*

If you lean back from your desk a bit in that small town in Canada’s north, Robert Service’s late nineteenth-century cabin comes into view. It’s a roughly hewn cabin, surprisingly bright inside—if the door is open. It’s just the right size too: one room for thinking, writing and cooking; one room for sleeping and reading.

Robert Service was a bank clerk, but he quit to write. Even he felt the tug of silence and solitude.

“I want to go back to my lean, ashen plains;” he wrote in that cabin.

“My rivers that flash into foam;

My ultimate valleys where solitude reigns; …

My forests packed full of mysterious gloom…”

*

You heard a theory once that people get tired when they exchange their busy urban lives for a weekend (or longer) in a quieter place, because the brain’s beta wave activity slows, adjusting to fewer stimuli—from frenetic and anxious to thoughtful, considerate. The usual clutter of human activity and productivity is replaced by a simplicity beyond the ego and control.

Don DeLillo wrote, “Cities were built to measure time, to remove time from nature. There’s an endless counting down.”

There is no counting down here. You pass a young guy practising his harmonica with one hand while walking down the town’s dusty, unpaved street. Early twenties, hipster facial hair, his other hand clutching a library book and a bag of bread made that morning at the bakery a few blocks over.

A dog lying in the middle of the road.

A cashier at the grocery store, checking her mascara in the reflection of a staple gun.

That kind of slow. Not a bank clerk or stockbroker in sight.

You hear another young guy, whose wristwatch is set two time zones to the east, describe the town as nostalgic summer camp for adults. It makes a kind of sense.

*

“I feel it’s all wrong, but I can’t tell you why—

The palace, the hovel next door;

The insolent towers that sprawl to the sky,

The crush and the rush and the roar.”

*

You wonder how the Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in must feel. Their land stolen and torn up in pursuit of gold, the caterpillar-like tailings from decades ago heaped as tall as the full-grown aspens that now stand beside them. The ground hollowed out, the silence shattered, the people whose ground it was banished downriver. The infinite landscape turned into infinite towering hummocks of burrowed dirt still there, visible from the air.

The first of the two planes that fly over the town and the tailings each day is a prop plane, en route to Old Crow and eventually Inuvik. This plane reveals the impossibility that flying is. Noisy, clunky, difficult. Ridiculous, even. A privilege.

The second plane, the one that comes in the afternoon, is a jet, full of cruise ship passengers from the Holland America Line, and when it flies over the town as it prepares to land, it feels and sounds like an F-16, blasting in out of nowhere, dragging its noise behind it, disappearing within seconds behind the mountains that hem the valley in.

*

On an island in the middle of the river a few hundred kilometres upstream of the town, you find a grave with a name carved into a rough, weather-beaten board a hundred years old.

R.I.P. L. Davis

You look at the mound, at the board fastened to an iron stake that serves as its tombstone, and you think of it in the winter, without visitors, without anyone to stumble upon it.

The river is wide and flat but deceptively fast, bulging at the horizon between two distant points of land, as though you’ve reached the end of the earth. Melting ice pans hit each other, clicking, clicking. It’s quiet enough to hear the clicking. The tops of the ice pans melt first, leaving most of the pan submerged just under the water’s surface, chunks shorn and layered like charcoal.

The natural rhythms of nature are tangible here, like tides.

Farther downstream a man waves from the forested shores, stopping you to say that someone jumped off a bridge into the river a few days earlier, just to go swimming, and never resurfaced. No sign of him even after four days of looking. “You keep an eye out,” he says to you, jerking his head downstream after a moment of silence. “It was my son.”

It’s only a few hours later that you wonder about the practicalities of finding a body. There’s no phone service for hundreds of kilometres, and the closest RCMP post is either Dawson or Carmacks, 400 kilometres apart, and you’re exactly halfway in between, in a canoe.

*

The Holland America tourists land at the town’s tiny airport, descending from the plane and walking directly onto pristine, temperature-controlled buses—the only vehicles in town without cracked windshields. Their luggage is directly off-loaded to avoid the small, cramped terminal that’s good enough for the locals. The simplicity of the town is seen as quaint and, yes, nostalgic by those who demand more.

By September, the temperatures drop quickly, snow starts to fall. The jets and the pristine tour buses stop coming; this is a reality only locals choose to endure. The small town in Canada’s north reverts to its original silence: a conspiracy of ravens chatting, the noon whistle, the occasional truck. Robert Service’s cabin sits empty—no more visitors to ponder the quiet, or the crush, and the rush and the roar.

You bicycle to the outskirts of town, by the gas station, where the plains hit the mountains pretty fast, where the giant coils of tailings fade and the landscape never ends. Without warning—whooshwhooshwhoosh—three cars rush past. You didn’t even hear them coming. One big, golden, two-door car, and two police cars in close pursuit, sirens wailing, kicking up gravel, the whole bit. Two hundred kilometres an hour, easy.

You stand and watch the chase for you don’t know how long before losing sight of them. They’re headed south, over a plateau stretched out like a never-ending carpet—what the rest of the town was like before the gold. The police are only a couple of car lengths off the other’s tail, and there are no other roads that intersect this one for the next 100 kilometres. You look up and see a group of sandhill cranes circling in invisible updrafts by a nearby cliff, their chirps and rattles floating down in the still air. After a couple of minutes another group of cranes appears, and the calling stops. The birds make their formation again, reconvened, and veer off silently southward, following the wake of the chase. You watch and you cheer them on, shouting out over that silent landscape, for once making noise.

Editor's note: The quoted text by Robert Service is from the poem "I'm Scared of It All," published in his collection Rhymes of a Rolling Stone (William Briggs, 1912).

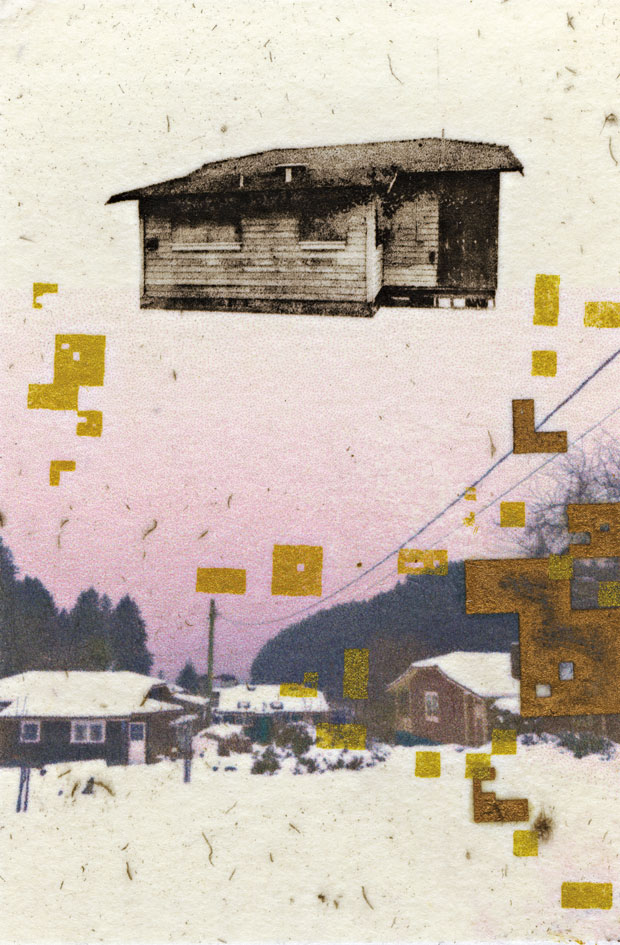

Image: Vanessa Hall-Patch, Cabin Cutout: Snowscape I, 2019, photo etching, screen print, digital, and chine collé