ONE

I apply for an artist residency at Maine’s Acadia National Park. My proposed project is a collection of poems grappling with the place of Maine in the Anthropocene. I write that I am interested in climate change, which I am, but only vaguely. It would be more accurate to say I want to be interested in climate change. I am accepted. But rather than an Artist-in-Residence—because I live in-state—I will be a Resident Artist. Instead of a traditional residency, which would include two weeks’ accommodation at Acadia’s Schoodic Institute, as a “local” I am encouraged to come and go as frequently as I want over the course of the year. I live a little over an hour away. I think about the gas I will use making the drive to a national park to write about climate change. I think about how frequently I want to come and go. How much gas does it take to drive ninety miles every day for one year?

TWO

Because I am Canadian and have a PhD in English, I am qualified to teach Canadian literature in the United States. At the graduate level. In the planning of my graduate literature seminar on Canadian dystopian fiction, I had assumed my students and I would become ecocritics, discuss climate change and mass extinctions, examine how writers conceive of worlds without ice caps and bumblebees. We would read of Omar El-Akkad’s imagined second Civil War fought over the use of fossil fuels. We would read of Margaret Atwood’s eponymous Crake engineering a global pandemic to save the planet from human beings. We would read of Pasha Malla’s Niagara Falls run dry, the pre-COVID-19 pandemics of Emily St. John Mandel and Thea Lim. But the students do not wish to speak of what these writers have to say of the world writ large. Instead, they coin useful phrases: “micro apocalypse”; “apocalypse at the molecular level”; “personal catastrophe.” In this way, they talk about the death of the self, individual dystopias, the end of a singular world.

THREE

I meet my first climate refugee at a brewery attached to a Chinese restaurant near the I-95 off-ramp. She tells me she recently fled the wildfires of interior Oregon. She has those sunglasses that dim and brighten of their own accord, the ones that always decide it’s sunnier than it really is. When I meet her she is jobless, she and her cat newly installed in a historic apartment on a street locals believe to be on the bad side of town. You moved here for neither love nor money? I am bewildered. Bangor, Maine, is not a big place, it does not draw a crowd. Academics like me move here to teach at the university twenty minutes away. Doctors move here to fulfill shortages. The rest seem to move away. The climate refugee talks about the research she did. This is the best place to live if you want a fighting chance. Months later, on Instagram, I watch the climate refugee prepare her newly purchased sailboat for a hurricane whose name I cannot now recall.

FOUR

My mother calls to tell me she read that the world is getting windier. She has a friend who purports to love the wind, claims it as her favourite weather. I am incensed by the idea of a windier world. My favourite weather is stillness, a temperature my skin doesn’t have to register as anything. I imagine beach picnics spoiled by sand in sandwiches, blankets refusing to be tethered beneath water bottles and shucked sandals, playing cards cartwheeling into the surf, my view of the ocean blocked by my own riotous hair. Whoever is with me chases a wayward towel along the shore, whoever is with me fails to come into focus. I should be glad my mother only wants to talk about the wind.

Have climate change activists tried the wind angle? It wouldn’t work on my mother’s friend, but still.

FIVE

My students are creative. They look up the meaning of the word “apocalypse,” discover the Greek word apokálypsis means revelation. Instead of talking about the end of the world, they talk about what is revealed. In a novel, it turns out, much is revealed. Apocalyptic revelations are typically mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, they read off Wikipedia. What is an author to a character but an otherworldly being, a god of a kind? We discuss what the authors reveal. When I try to steer us toward the authors’ politics, they jerk the wheel back to apolitical gods of prose and character development, plot structure and metaphor.

SIX

The poet Franny Choi writes that she cried when she saw photos of the bleached coral reefs, writes that she had to cut the same phrase from every poem she wrote: Bleached reef. Bleached reef. I understand completely. The assonance appeals. Those seductive vowels. The World Wildlife Fund says I can help protect coral reefs by taking simple steps like carpooling to work.

In lieu of solitude, I carpool us losers, us fools. I toot my own horn poorly, boorish. I eschew, I renew. I brew kombucha, save the belugas. Soon I am doomed too.

What I will have to cut from every poem: Doomed too. Doomed too.

SEVEN

My students decide a text with any kind of loss is fair game: a death, a breakup, even a graduation is the end of the student self. It is all apocalyptic fiction, they conclude. Maybe they mean that all of literature is apocalyptic. Who am I to argue with their logic? But what does it mean, I wonder, that they don’t want to talk of extinction and pandemics and overpopulation and natural disasters? That they multiply apocalypses and dystopias using the phrase “granular scale” until every conflict is an end that must be spoken about with the gravitas we typically reserve for mass death? What does it mean that they don’t want to talk about Atwood’s depiction of hyper-capitalism? That they instead want to locate the true end of the narrator’s world as the moment his mother abandons the family?

EIGHT

On my drive along the Schoodic Scenic Byway, NPR tells me to check on my neighbours this weekend. It is early October, usually a safe time weatherwise, but Tropical Storm Philippe is scheduled to bring rain and high winds landward. No, I realize, it can’t be Philippe. The meteorologist is talking about temperatures in the nineties, hundreds in the valleys and deserts. This is a national segment. It’s Southern Californians who are supposed to check on their neighbours. Heat waves, forest fires, something something, the Santa Ana winds. I tune out, my own neighbours presumably fine. I start looking for trees along the byway that have flipped their switch. Maine’s foliage map, reporting colour change and weekly leaf drop, says leaf-peeping conditions are approaching peak, and I am ready to be dazzled by a golden, inert storm. If an otherworldly being wants to reveal something to me via burning bush, I will allow it. I will take a god of any kind.

NINE

But what do these authors have to say about neoliberalism? I ask the class. How can we approach these texts through an ecocritical lens? I almost project photos of bleached coral reefs onto the screen of our seminar room. Are we, like these characters, doomed too? Are we, like these bleached reefs, doomed too? I want to yell about the Santa Ana winds, about wind in general, but the truth is I’ve been paying such little attention. If NPR doesn’t run a segment on one of the various ongoing global climate crises while I happen to be driving, I am likely oblivious. Besides, how could the students know why I am desperate to return to the big picture, the one with the rib-visible polar bear dragging himself across a browned-out tundra? How could the students know I am in the midst of my own myopic dystopia, that one of my singular worlds has collapsed? How could they know I want to be distracted from the fact my husband and I are living in separate houses, that I need something—something like a massive oil spill, something like a flood that’s levelled a city the world just learned the name of, something like a forest fire that ate up the better part of a continent—something that I could say with some degree of certainty is not my fault?

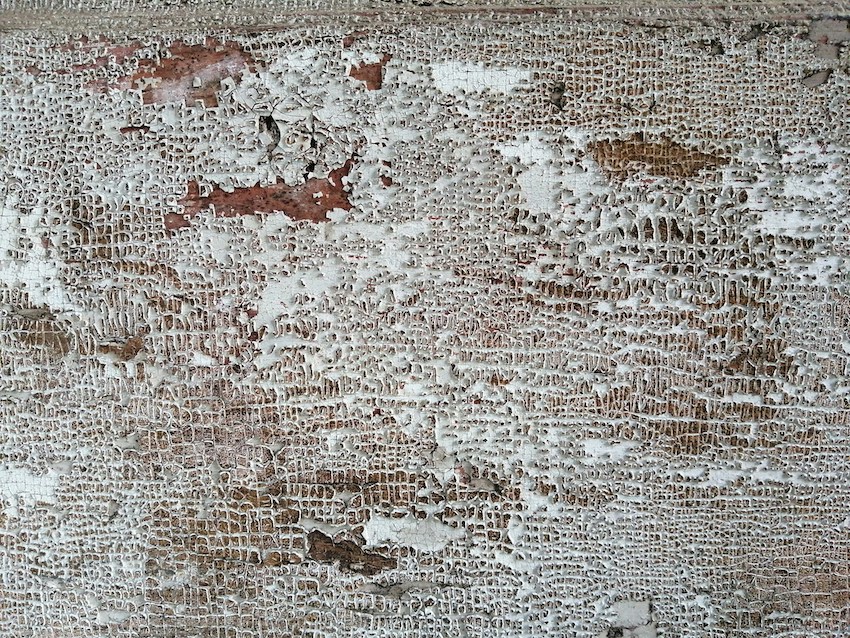

Image: TREY FLOZ, The Future Is So Bright, 2020, digital illustration