Great-great-grandmothers, I am writing to tell you I made it. You made it.

We survived.

Picture your Egyptian great-grandson meeting your German great-granddaughter. They have a couple of kids and immigrate to—wait for it—Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Now I, their daughter, live in a picturesque city colonially known as Victoria, British Columbia.

You might not know where that is. You probably thought of Canada as often as I think of Eritrea, Latvia or Uruguay. Maybe you’d heard of it and pictured igloos. Now you’re here, and when (if?) my great-great-grandchildren trace their DNA, they will be surprised that you existed at all. Their future history is entangled in your mystery, and I am their unreliable bridge.

I traffic deep time in a great storm, guilty of ignorance and omission. I write the lines of a third-culture immigrant whose sense of belonging was exported for new opportunities. My father told me to be grateful and I am. Can you imagine yourself in a hijab? With that big mouth of yours? You’d have been stoned to death, you stupid girl.

I rewrite ancient tales of the Sumerian goddesses Inanna and Ereshkigal and how they navigate the Underworld. My sons stuff my stories into their pockets. I know death enough to know that they’ll find my crinkled-up pages after I’m gone. They’ll bring out their flashlights and look for the meaning I’d hoped to impart. If they can’t find it, they’ll make something up. Something about hubris and climate change. Something about civilizations making the same mistakes over and over again. A bit about sacrifice and how much I love them. One of them might wonder, Didn’t she say something about reverence?

When asked where he was from, my father would say, in his thick and ambiguous song, Edu-mon-ton. You want to see my passport or something? My mother said nothing, to hide her accent. My sons say they’re from here and no one bats an eye. They live comfortably on stolen land and barely grapple with their privilege—everything my formerly occupied father hoped for.

Grandmothers, I tell my boys stories I’ve made up about us. Like, when I make bread, I pretend I come from a long line of bakers. Maybe I’m a puppet, and you pull my strings. I want to believe my hands hold your memories—that you followed us here.

But where are you really from?

Edu-mon-ton?

I like to imagine that my real parents are the reeds between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, but I was born in a coal mining town called Gelsenkirchen and given an Egyptian passport. I’m the daughter of Hosam El-Din Ibrahim Hassan, Ursula Mowe and Pierre Elliott Trudeau. I’m from the coldest day of 1968, but not the psychedelic, free-loving, bra-burning ’68 of our California dreams. No, I’m from a sober, post-war, obedient virgin who jumped into action the second her angry husband screamed. I’m from her capitulation. I’m from the grief of losing my daddy.

I remember my German accent and my father’s brown skin. I can count, swear and pray in Arabic, but don’t know the difference. I shocked my cousins when I unknowingly called their mother a whore, believing that I was counting to ten. Als ich fünf Jahre alt war, dachten die Deutschen, ich sei ein Einheimischer, but now I stumble over those words.

I grew up hearing about drunk Indians who didn’t pay taxes. Not a word about residential schools by the time I graduated high school. Canada’s origin story was delivered with colorful cartoon characters that looked like ancient history. There were the Indians (them); running naked savages, cutting off each other’s heads, and the settlers (us?); white, clean, organized folk who just wanted a better life. I was told we belonged to this country more than the Indians, but not and never as much as my friend Susan, whose British family had been here for five generations and had helped lay the foundation for this fine nation. We were betwixt and between, working overtime to fit in.

After speech therapy, after boobs, full lips and tanning easily, I was so popular that I walked ten steps in front of my parents. It was like I’d never even met them.

This is how to become Canadian: forget everything.

(Grandmothers, what were your names again? I’ve looked and I’ve looked, but I can’t find them.)

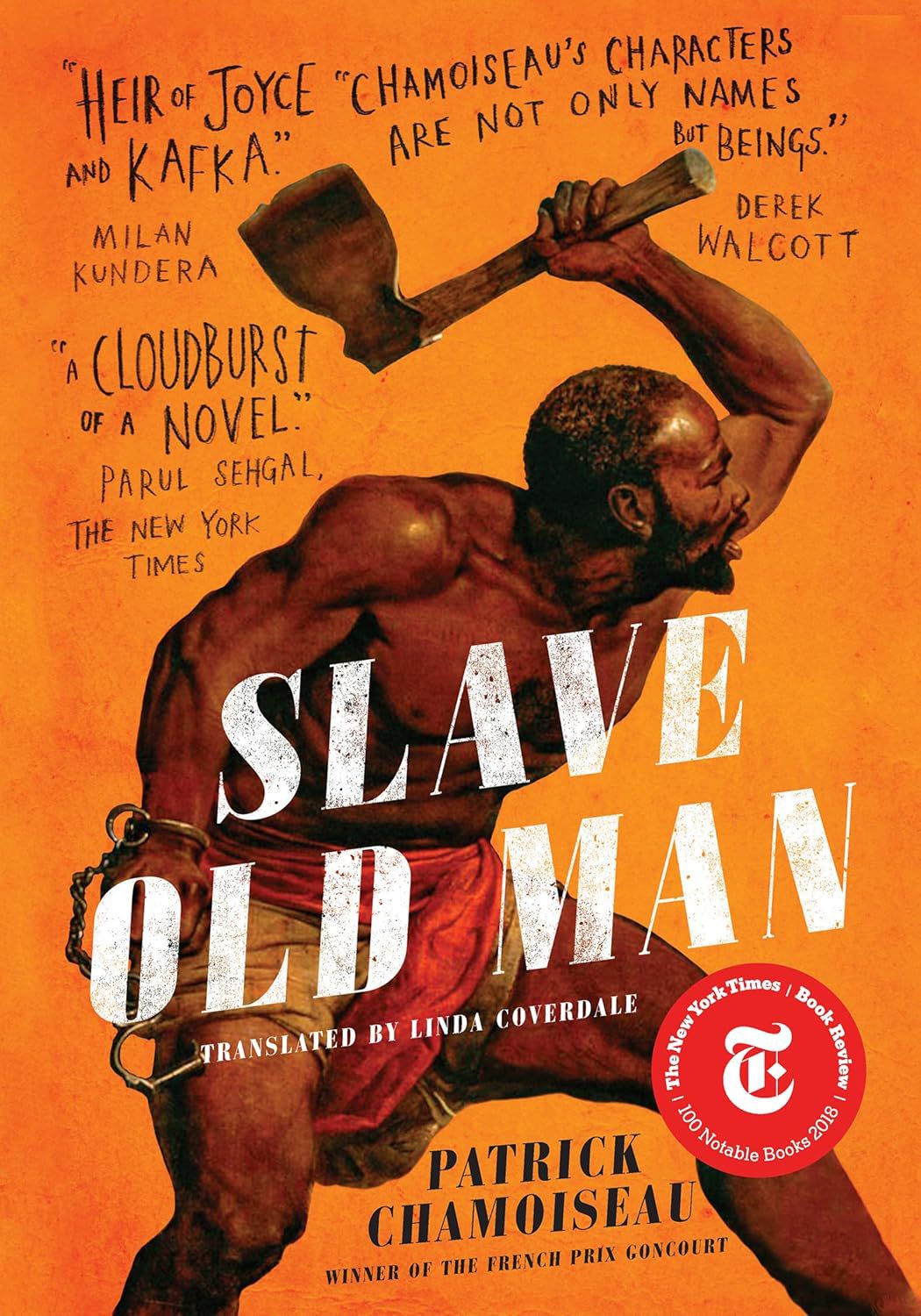

Image: Sarah Snip Snip, Banff Mini-Stamp, 2023, analog collage