In our nearly ten years of correspondence, Santa Claus had not once mentioned his cousin, Gandalf the Grey/White.

There was probably an element of rivalry to the whole thing; they were both wizards, sure, but strip back the layers of time and Gandalf is still Gandalf. Rub off the sheen of Coca-Cola ads and Rankin/Bass animation, however, and Santa Claus is forever that hinterland oddball, Radagast the Brown, communing with squirrels and brewing herbal concoctions in the glen. It must have softened the blow when hundreds of elves, exiled from their millennia-old home in the woods of Lothlórien, chose to follow him to the North Pole to start a new elvish settlement. Galadriel (forever the ultimate Good Witch in my hazy hagiography) took up the sexless post of Mrs. Claus to Radagast’s Santa.

At age ten, my bizarre mishmash of folklore, pop culture and Tolkien became something like religion to me, aided by a string of Christmases in which Santa granted my increasingly bizarre requests.

Because he could do anything. Because, unlike some of the other adults in my life, I could always depend on Santa.

Exhibit A: Magic Wand

It started out small, at age five: a magic wand that could “really truly grant wishes.” A reasonable request of a being who possessed infinite power. But on Christmas morning I woke to a wooden dowel, gold-painted stars clumsily hot glued to the tip. And an explanation from Santa, printed on expensive-feeling cream cardstock.

The magic wand, Santa explained, was impossible. Thousands of years ago, there had been a great war between the forces of Good and the forces of Evil, fought over who would get to hold and wield magic wands. It was a gruesome war, Santa added in Papyrus font, but the forces of Good eventually emerged victorious. To ensure this dark period of history could never be repeated, the forces of Good eradicated all magic wands, and everyone lived in peace for thousands of years.

Santa Claus had just linked his own world to the world of Lord of the Rings, though I didn’t know it yet. I kept his letter in a drawer near my twin bed and frequently pulled it out to ponder it, like a Gideon Bible in a motel nightstand.

Exhibit B: Pink Flamingos

The year I decided to test Santa by asking for pink plastic flamingos (the kind that invade a work friend’s lawn on their fiftieth birthday), he delivered two of them to the front of my grandparents’ house, each perched one-legged in the snow beside the slumbering hostas. I was six, but I beamed like I had just discovered a new periodic element. My grade 1 teacher (a popular villain in my grown-up nightmares) had something else to say. In my class journal I wrote all about how Santa was invincible, how he had improbably brought me the weird thing I had asked for. Her response in the margins, in cramped teacher’s handwriting, was, “Your parents were very clever to get you those flamingos.” How tragic, I thought, that this woman had never known the magic of Santa. O ye of little faith!

Exhibit C: Fairy Dust

The magic wand had been a dud, but at seven I tried again with fairy dust (so that I could fly, obviously) and waited with eager certainty. But that Christmas morning, I received an empty velvet bag with a smattering of glitter in the bottom, and a note from Santa. He had run out of fairy dust for the sleigh and had to borrow mine to make sure Rudolph could keep flying. He gave me his bell to thank me—an enormous, scuffed-up and credibly antique livestock jingle bell. Santa hadn’t let me down, though—by including me in his flight plans, he ensured that I felt closer to him than ever.

Exhibit D: Inflatable Couch and Rubber Chicken

Grandma’s new hairdryer was mysteriously broken on my eighth Christmas morning, but my green inflatable couch was fully blown up in my grandparents’ living room, and the rubber chicken I’d asked for waited expectantly under the blue-lit Christmas tree. There weren’t any notes from Santa that year, but I didn’t need them—by then I fully believed in the Big Guy, all furry red suit and quadruple-bypass waistline, and I proselytized enthusiastically for the Cause of Claus. He was a grown-up I could depend on, maybe even confide in one day if I met him.

Exhibit E: IKEA Side Table

The year I broke my ankle on uneven blacktop, I read The Hobbit for the first time and all the nebulous pieces of my belief system began to click into place. My book report that year was a page protector over a facsimile of the Lonely Mountain made entirely from beans and legumes—white navy beans for the peak, brown lentils farther down. I’d made the connection that Santa came from Tolkien’s Middle-earth, and I treated the project with reverence usually reserved for the live Nativity at church (braying donkeys, squealing infant, the whole nine). Because of the broken ankle, I spent most recess periods inside, propped up on brought-from-home pillows—my own version of the Lonely Mountain.

My other fixation that year was IKEA. I obsessively watched old episodes of Trading Spaces and then pored over the IKEA catalogue to find decor that matched. And I made lists. So. Many. Lists. Not just of “a chair” or “a sofa,” but “EKTORP Sofa, $997.99.” That Christmas I asked Santa for IKEA furniture, but I also told him I’d rustled his Radagast the Brown secret and that he didn’t have to worry. I wouldn’t reveal something so sacred to anyone. I received two triangular LACK side tables ($14.99 each), and I had never felt so loved or understood. I started reading The Fellowship of the Ring.

Exhibit F: Marge Simpson Wig

For inexplicable reasons, my TV-hawk mother allowed me to watch The Simpsons at age ten; I simultaneously had a strong fascination with wigs. I was also elbows-deep in Tolkien lore and knew with a lacerating certainty that the elves of the North Pole were the same elves as the ones from Lothlórien, their lithe and slender frames warped and distorted by mainstream media. Or maybe the elves themselves were responsible for the sleight of hand (sleigh of hand?) PR campaign, doing everything they could to obfuscate the truth.

But I knew. I wrote to Radagast and Galadriel and requested a Marge Simpson blue beehive wig. If they delivered a gift requested under their true names, I reasoned, that was tantamount to admitting the identities they’d been hiding. I waited patiently. Lovingly, even. I was barely surprised when Santa left the Marge Simpson wig beside the treeful of twinkly blue lights. I had the most forceful connection to the Big Guy that day—one of the closest things I have ever felt to holiness. I was old enough that most of my classmates Knew About Santa Already, but I brushed off their naysaying like so much lint; they didn’t understand Santa Claus/Radagast the Brown in the intimate and profound ways I did. They hadn’t tested him as rigorously, and thus hadn’t felt enough of his all-encompassing love.

I was more sure of his magic, it’s true, than I had ever been sure of myself.

Exhibit G: The Father Christmas Letters

One day, about a week after Christmas, I was rooting around in the bedroom that had been my sister’s before she decamped for university. I found not-quite-put-away-yet holiday decorations (in truth, our dusty tree stayed up all year, smothered in hearts on Valentine’s Day and bedecked in eggs come Easter), beat-up old shoes of my sister’s that were no longer in service. And a bag. A semi-transparent plastic shopping bag, through which I could clearly read the magical name Tolkien and trace the sharp right angles of my favourite object (a book!) with eager fingers. The title was The Father Christmas Letters.

I grabbed the bag and ran to the kitchen, where my mother was taking notes on a radio show.

“Did you know there was a new J.R.R. Tolkien book? And it has pictures!”

Her head snapped up as though she had been electrified. She flicked off the radio (not a common occurrence; to this day, my mother likes to keep a radio on in every room, so she doesn’t miss any of her favourite CBC programs).

“It’s Tolkien, Mom!”

“Yes, it is,” she said, her upper lip tense. “We need to talk.”

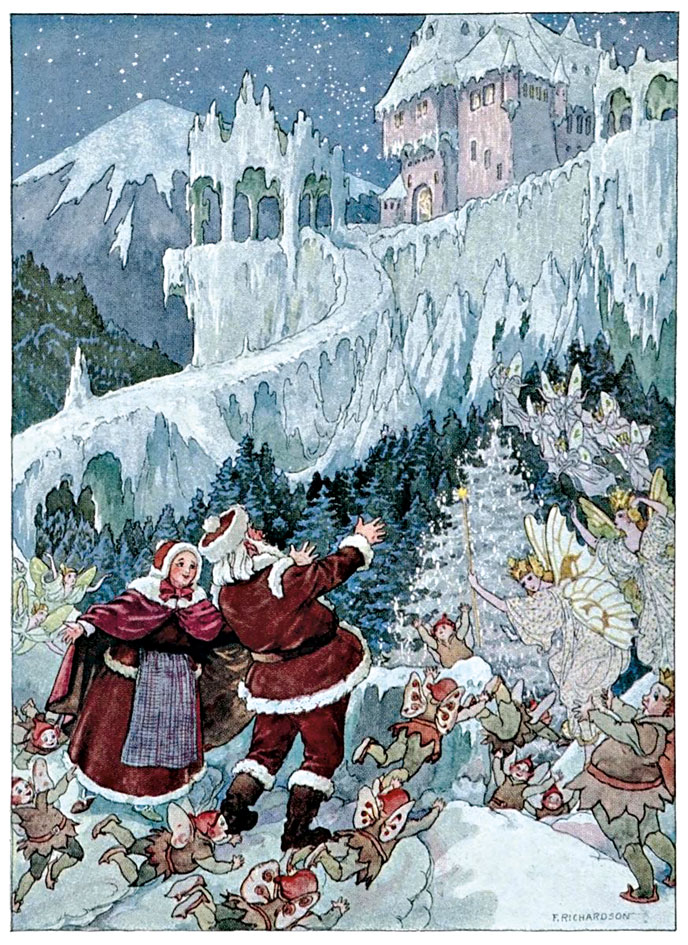

Image: From Christmas Stories by Georgene Faulkner, illustrated by Frederick Richardson, published by Daughaday and Company in 1916