fact

Gangly Man

I don’t take public transit very often, which is a failing—not just environmentally, but also personally, because sometimes that forced contact with the rest of the populated world can be profound. In Japan, many years ago, I was trapped in the small space between train cars by a crowd of schoolboys; my claustrophobia reached such a level that one leg began to judder up and down like the needle on a sewing machine, and the only thing that prevented me from climbing out over the tops of my fellow passengers’ heads was the gaze of a man about a foot away who conveyed calm to me by keeping his eyes trained on mine.

Witch Hunt

In a letter of 350 words, published in Geist 65, Michael Redhill calls me a racist once and implies that I am a racist on at least four other occasions. Redhill’s repetition of the ultimate insult of the postmodern era offers a fascinating, if depressing, window into how certain Canadian writers betray their responsibility to the society they live in.

Van Gogh’s Final Vision

Auvers-sur-Oise is a town of ghosts. Among the summer tourists and art-loving pilgrims who visit Auvers from all over the world, drift flocks of long-dead artists with folding easels and boxes of paints, who a century ago would disembark every week at the small railway station.

The Self-Destruction of the CBC

The federal government recently announced it is reviewing the CBC’s mandate. This review is the latest chapter in a long story of questioning the value of the CBC since its inception seventy years ago. Clearly there are politics involved here; the CBC is an easy target for attack by parties of all stripes.

The Lights of the City

The theatre is plush, high-ranking and named after the Queen. I don’t know the name of the play but C does. C brings me to the theatre when I go. I undergo a pleasant transformation when I go to the theatre. I wear a tie, black shoes and a sports coat. At first it was difficult, “not my style.”

Phenotypes & Flag-Wavers

Last summer, in anticipation of the opening round of the World Cup of soccer, the largely immigrant population of the narrow side street in Lisbon where I was renting an apartment draped their windows with flags. The green and red of Portugal predominated, but the blue planet on a gold-and-green background of Brazil also hung from some windows.

The Definite Article

The top-selling American novel of the nineteenth century was Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The phrase “the Christ” reminds us that the second word originally meant something along the lines of “the person who has been anointed.” By the twentieth century, the article had been dropped, making “Christ” sound like the family name of Sometime Carpenter Jesus, offspring of Joe and Mary Christ, brother of Jim Christ who keeps cropping up in the New Testament. But a couple of generations after Jesus lost His definite article, His spokesmen on Earth were still “the Reverend” So-and-so or even “the Reverend Doctor” until the editors of Time and their kind followed Samson’s example and warning: metaphor ends in 25 metres—smote them with the jawbone of an ass.

What?

At home Frank and I are mutually sympathetic to the obligation to face one another and speak loudly; or, when we are away, to supply each other with new batteries when we forget them; but we have no defence against the independent wandering behaviour of our hearing aids. They are always someplace else. I probably have spent one percent of my life, close to a whole year, looking for the damned things.

.svg)

Snail Mail

I’m sorry, but you cannot mail any box with writing on it. I see. Perhaps you have a marker with which I can cross out the writing? No, we have no markers here. Perhaps you have some packing tape we can put over the writing? No, we have no packing tape here. How about some of that special blue-and-yellow postal service tape I see there? No, no señorita, you cannot put special blue-and-yellow postal service tape just anywhere.

Window Booth at Rapido

A group of university exchange students from France at the next table watch the entire interaction as if they were on a field trip for Lessons in North American Social Behaviour. They discuss the annoying aspects of the life they’re having here. Quebec is more American than they expected, they say. You can’t smoke in restaurants. The Québécois accent is drôle.

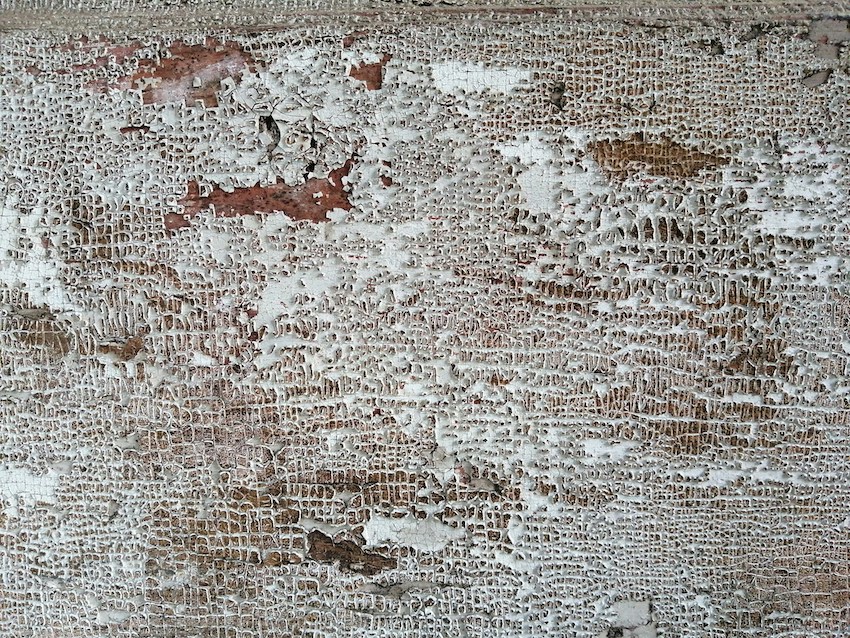

Re-hanging the National Wallpaper

When I lived in Ottawa in the 1970s, I used to enjoy passing lazy afternoons at the National Gallery looking at the pictures. I remember how surprised I was when I first encountered the Group of Seven collection. These paintings were completely familiar—I’d seen them in schoolbooks and on calendars, posters, t-shirts, everywhere—yet at the same time they were completely unexpected.

.jpeg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.jpg)